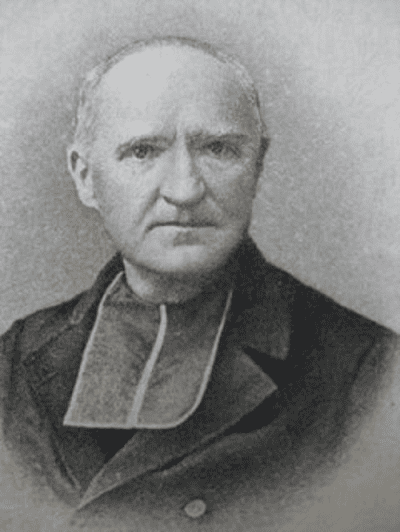

John Baptist Hogan, pss (1829-1901)

Bernard Montagnes, O.P. , in his biography of Dominican Father Marie-Joseph LAGRANGE underlines just how much the last year in seminary formation at the Seminary of Saint Sulpice influenced the exegetical vocation of the future founder of the famous Ecole Biblique in Jerusalem. He, among others, such as Pierre Battifol, Henry Hyvernat and E.-I. Mignot, future Archbishop of Albi, benefitted from the instruction of several Sulpicians, especially Father John Baptist Hogan.

The life of this last named is rather exceptional. Born of an Irish father and French mother from Périgord, Hogan’s uncle, a priest of the Diocese of Périgueux and Sarlat, invited him to do his ecclesiastical studies in France, first at Bordeaux and then at Séminaire de Saint Sulpice in Paris. Ordained a priest at nearly 23 years of age on 5 June 1852, he decided to enter the Society of Saint Sulpice. His numerous abilities were quickly noted, such as a facility with languages and a well formed personality, with an exceptional ability to listen. His psychological makeup quickly earned him the esteem of several significant people of the day: Charles de Montalembert, Felix Dupanloup, Albert de Mun, among others.

To this one should add that his perfect bilingualism gave him the opportunity to be in contact with significant figures of the “Oxford Movement,“ whether on the Catholic or Anglican side. Certainly these exchanges, which progressively developed, made him aware of the necessity to know the scriptures better and to make them known better, in particular, the discoveries of the Tübingen school. This was a far cry from the fastidious paraphrases of French seminaries of the era, of which his confrere Louis Claude Fillion was so emblematic.

In 1884, at 55 years of age, he responded to a call to take over direction of the seminary in Boston. Then five years later he was sent to participate in the founding of the Sulpician seminary in Washington, of which he became the first superior. In 1894 he was recalled to Boston as adjunct superior to James Driscoll (1959-1922). But he became sick and returned to France in 1901, where he died not long after, on 30 September 1901.

How did Father Hogan integrate scripture into his teaching in such a fashion that he so struck those who would become masters of the “Catholic reform” movement in exegesis, such as Lagrange, Hyvernat , Driscoll, Battifol, and numerous others?

A passage from the letter of the Superior General at the time of his death recalls the essential traits of Hogan’s pedagogy: “Although his teaching remained ever classical in style, he dreamed of a way to make scripture more applicable, attractive and useful. Some of his students at times desired more precise solutions, more unchangeable rules, more affirmations and fewer questions. Father Hogan, however, was more preoccupied with a desire to stimulate and open the spirit [of his students], to make them think for themselves, to form their own judgments for the application of principles. A lot of priests retained a profound recognition of the intellectual profit he pulled from them. Nevertheless he rendered his teaching more universally useful by insisting on various theses and giving fewer objections than his spirit was inclined to have.” This appreciation already speaks volumes about the radical change in method promoted by John Hogan.

But one should also recall the position of the Superior General of Saint Sulpice, M. Jules Lebas, at this particular time. It was not only method that was in view but also content. In 1901 we plunge into the “modernist crisis” in which Father Lagrange was already implicated, and the Sulpician seminary in New York had begun to be a place of intellectual ferment that finally exploded in 1905. In the same year (1901) M. Lebas was elected Superior General after the resignation of M. Arthur-Jules Captier – who was very close to John Hogan – and assumed a more reassuring profile with regard to theological orthodoxy. It is certain that M. Lebas had already for some time put the brakes on ideas he considered new theories regarding to the Bible, in particular during his long tenure as superior at Lyon.

At its very foundation, was the departure of Father Hogan for Boston a sort of “sacrifice,” as the official documents of the Society indicate, or a disguised way to get him out of France? Like the adage promoveatur ut moveatur (promoted in order to be removed). John Hogan was first marked by the thought of Henri Lacordaire and Felix Dupanloup, as well as by the way in which John Henry Newman was conceiving the development of Christian dogma. Hogan also was aware of the works of Germans like Johann Adam Moehler and his successors at Tübingen. Finally arriving in the USA, he understood perfectly the debates that were happening in seminaries at the end of the 19th century. Confronted with the plurality of expressions of the Christian faith lived in the new continent, he perceived with all acumen the necessity of a solid formation in sacred scripture. Also, during his tenure as superior in Washington, he entered into a distant epistolary relationship with the thinking wing of modernism, like Maurice Hulst and Alfred Loisy himself. His work Clerical Studies then became suspect by Roman authorities.

The death of Father Hogan did not change the situation in the USA. On the contrary! One of his former students, James Driscoll, having taken his biblical formation under Father Hyvernat in Rome, was named superior of the seminary in New York in 1902. The latter became well known for his translation of the book by M. Albert Houtin, The Biblical Question among Catholics in France, which was placed on the Index of forbidden books by the Holy Office in 1901. In New York, M. Driscoll found his formation team well trained and qualified in sacred scripture, and also very influenced by the discoveries in the new exegesis. Certain teachings are even “Orientalist” of the first order. By this biblical and Oriental “openness” the seminary in New York appeared to be a center for “avant-garde” thought in the United States. The publication of a periodical (Dunwoodie Review), in which would appear the names of the individuals most implicated in defending the new theology, created a violent conflict between the Superior General of the Society of Saint Sulpice and the Provincial of the U.S. Province. This conflict finally resulted in the decision of almost all of the faculty members of the seminary to resign from the Society of Saint Sulpice and to remain as priests in the Archdiocese of New York.

This image of Father Hogan is not well known in the history of the Society and beyond, but it helps us consider the question of how the teaching of the Bible was born and then progressed in certain ecclesiastical contexts in France. Hogan was not only a biblical scholar, but he understood the theological concerns and questions of his day – following the works of Tübingen and Oxford – and he knew how to stimulate the movement which made Lagrange, Hyvernat, and Battifol create a certain radical “Wendepunkt” (turning point). In this sense, Hogan would deserve further scrutiny by experts.

N.B.: This article by M. Philippe MOLAC, pss, a Church historian of the Society of Saint Sulpice, is copyrighted (© 2012) and cannot be reproduced in any form without the expressed written permission of the author.