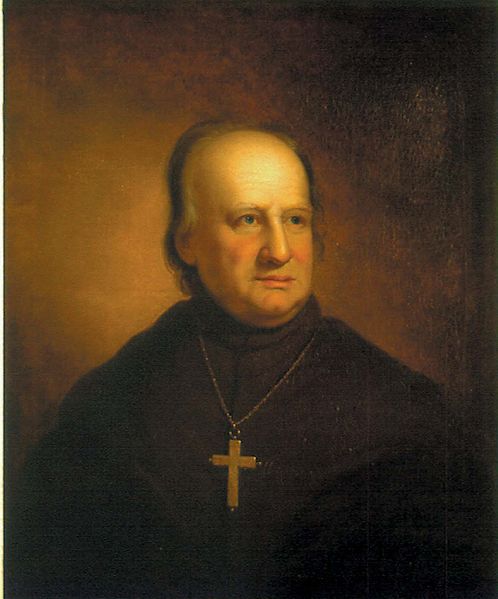

Ninth Superior General

April 28, 2011 marked the two hundredth anniversary of the death of one of the most remarkable Superiors General the Sulpicians have ever known, Father Jacques-André EMERY, pss, the ninth Superior General of the Society of the Priests of Saint-Sulpice (1782-1811). The bicentennial passed without any fanfare, but the importance of Father Emery in Sulpician history is not forgotten.

Born in 1732 in Gex near the Swiss border, Father Emery studied philosophy at the Sulpician seminary in Lyons and then entered a house, Les Robertins, attached to Saint-Sulpice in Paris, and studied theology at the Sorbonne. He entered the Sulpicians and was ordained a priest in 1758. He then served in the seminary at Orléans. After completing his doctorate from the University of Valence in 1764, Emery was assigned to the Sulpician seminary in Lyon to teach moral theology. There he gained a reputation for discipline, holiness, and academic excellence. He also published several noteworthy works, especially a book on Gottfried LEIBNIZ (1772), the German philosopher and rationalist, and a spiritual tract on Sainte Thérèse d’Avila (1774) (both pictured).

Obviously, the times in which Father Emery exercised his priestly ministry were very trying. Rationalism was making serious inroads in the traditional authority held by the Church, and serious social unrest in France, which eventually led to the French Revolution in 1789 and the subsequent Reign of Terror (1793-1794), was mounting. Moreover, as Superior General in the time of Napoleon, Emery was caught in a strong political game being played out between Church and state.

Like Father Jean-Jacques OLIER before him, Father Emery was ascetically inclined, personally devout, and preoccupied with the reform of the clergy and the maintenance of a strict code of priestly formation. He thus was known for his firm leadership in the seminaries in which he served.

In 1782, upon the resignation of the Superior General, Father Pierre LE GALLIC, for reasons of health, Emery was elected Superior General and automatically also superior of Le Grand Séminaire, where he saw the need to reinstate discipline in a rather lax environment. Although one could point to numerous achievements of Father Emery, three aspects of his time as Superior General stand out.

First, Father Emery’s personal holiness and ascetical manner, as well as his openness to the more mystical experiences of faith, made him a superb model for the priests and seminarians whom he tried to hold to a high standard. In the reforming spirit of Father Olier, Emery evoked the need for fidelity by personal example and not simply by word.

A second inspiring aspect of Father Emery’s time as Superior General was the nature of his leadership. His dignified and firm manner nevertheless was balanced by an ability to adapt to the demands of his time. A prime example of this dual tendency is his response to the requirement to take the secular oath for equality, fraternity and liberty that resulted from the French Revolution. It was widely viewed by priests and bishops as a direct affront to the Church and papal authority. Others too easily accommodated the oath and became very secularized and rationalist. Emery took a very moderate position. He took the oath and advised other priests to do likewise because he saw it as a vague promise to uphold the civil realities rather than a direct opposition to ecclesial authority. Thus Emery is a model of adaptation and moderation in the midst of excesses. One might say he discerned “the signs of the times” and adapted to them, but not in ways that compromised his faith.

Finally, a third aspect of Emery’s leadership was his ability to take risks. He feared that the Society of Saint-Sulpice might not survive the persecutions that came upon the clergy during the Reign of Terror and during the tense regime of Napoleon. Thus, he encouraged Sulpicians to emigrate to other locales, most notably to the United States, where he sought out and favorably responded to Bishop John CARROLL’s desire to have a seminary founded to train native clergy.

Carroll was the Bishop of Baltimore, the new nation’s first Catholic diocese, established in 1789. St. Mary’s Seminary was founded in Baltimore in 1791, with the arrival of four Sulpicians and five seminarians sent from Emery as the foundation for the new endeavor. The risk was evident in such ventures, but Emery tried every creative means to ensure the survival of the Society.

Father Emery paid for his visionary leadership. Unlike many priests who fled France, he stayed in Paris and was imprisoned twice during the Reign of Terror and was bullied by Napoleon, who nonetheless had great respect for him and perhaps no little fear of him as a formidable and saintly man. Testimony from that era indicates that Emery was one of the most respected and influential priests in France, despite the excessive anti-clerical fervor that followed the French Revolution. He bolstered the faith of other priests in the face of such trials and tribulations.

Worn out physically and emotionally, Emery died on 28 April 1811, clearing the path for Napoleon to suppress the Society of Saint-Sulpice and close Sulpician seminaries in France. Emery’s fears were thus realized for a time, until 1814, when the order for the Society’s dissolution was reversed after Napoleon’s abdication.

This short summary of Father Emery’s importance does not do justice to his true greatness. Yet it does give a glimpse of why it is worth recalling this bicentennial. Sulpicians today consider Father Emery virtually the “second founder” of the Society, for he is the Superior General who enabled the Society to survive, despite the grave dangers faced in his day.

May his inspiring example live on in his Sulpician heirs today!

For further information on Father Emery, one can consult the following:

Christopher J. KAUFFMAN, Tradition and Transformation in Catholic Culture (Macmillan, 1988), 33-41, 59-63.

Philippe MOLAC, Histoire d’un dynamisme apostolique : La Compagnie des Prêtres de Saint-Sulpice (Cerf, 2008), 77-93, 96-100.

Pierre BOISARD, La Compagnie de Saint-Sulpice : Trois Siècles d’Histoire Vol I (Paris), 181-203.

F.-M. PHILPIN DE RIVIERE, Vie de M. Emery, neuvième supérieur du séminaire et de la compagnie de Saint-Sulpice [par J.-E.-A. Gosselin], précédée [d’une notice sur l’auteur et] d’un précis de l’histoire de ce séminaire et de cette compagnie depuis la mort de M. Olier [par Philpin] (Paris: A. Jouby, 1861-1862).

Elie MERIC, Histoire de M. Emery et de l’Eglise de France (2 vol.; Paris : V. Palmé, 1885).

Jean LEFLON. Monsieur Emery. L’Église d’ancien régime et la Révolution (Tome 1; Paris: Bonne Presse, 1945).

Jean LEFLON. Monsieur Emery. L’Église concordataire et impériale (Tome 2; Paris : Bonne Presse, 1946).