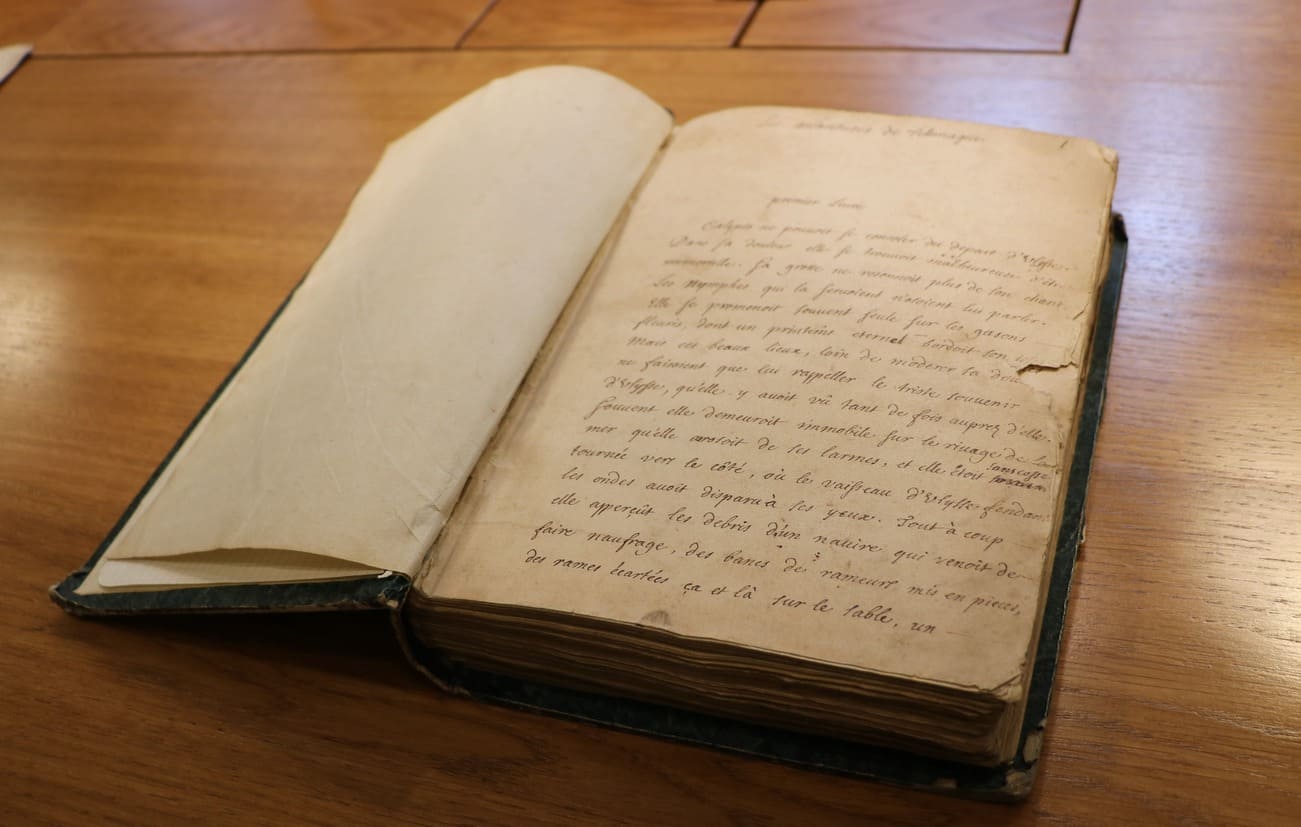

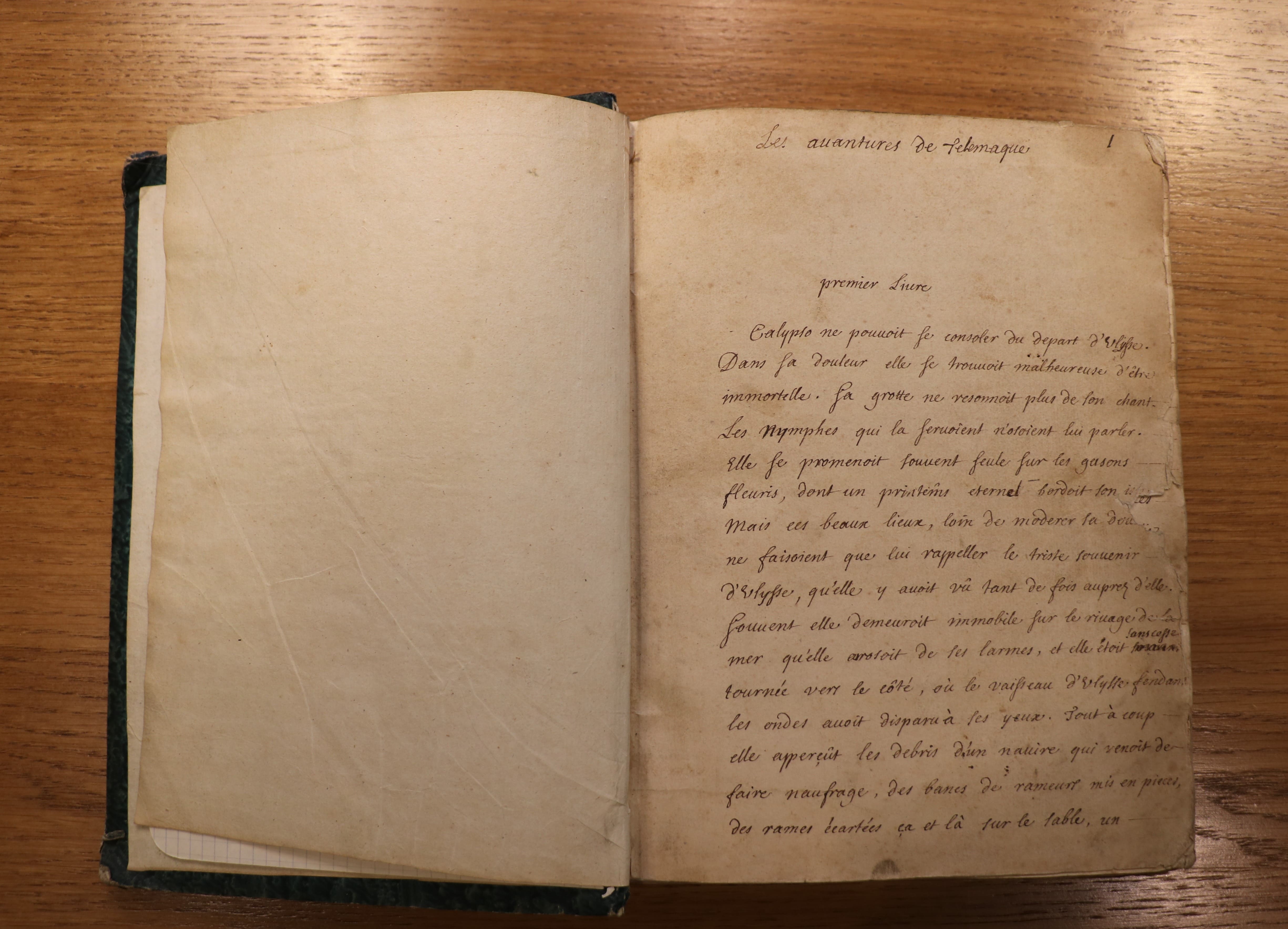

Archives of Saint-Sulpice, manuscript 2028

Since the publication in 1699 of The Adventures of Telemachus (Les Aventures de Télémaque) by the famous François de Salignac de La Mothe Fénelon, there have been more than 550 reprints of this bestseller from the end of the 17th century—not to mention translations into other languages, including outside Europe. These estimates, likely well below reality, allow us to recognize the exceptional success of this book.

It was probably around 1692 that Fénelon had begun writing his initial novel. It appeared for the first time in 1699 without the author's permission, under the title “Continuation of the Fourth Book of Homer's Odyssey or the Adventures of Telemachus, Son of Odysseus.”

The book was in line with other educational texts composed by Fénelon, the tutor to the Duke of Burgundy, in order to educate young Louis of France, grandson of Louis XIV.

We know that copies of the text began to circulate first within the families of royal blood. Then it made the rounds in the royal court from the autumn of 1698, at a time when its author found himself in difficulty because of another of his publications the previous year. This was his Explanation of the Maxims of the Saints on the Interior Life, in which he defended the positions of Madame Jeanne-Marie Guyon in the so-called debate on Quietism. This controversy placed him in direct opposition to the famous preacher and Bishop of Meaux, Jacques Bénigne Bossuet, before Rome condemned him, in turn, on March 12, 1699.

At the same time, the publishers were attempting to publish The Adventures of Telemachus, copies of which continued to circulate secretly. This is how the widow Barbin managed to obtain a royal privilege on April 6 of the same year, in order to publish the first volume. But, as soon as it appeared, rumors about the novel’s subversive nature led Chancellor Louis Boucherat to have this privilege revoked, thus preventing any reprint.

The immediate success of the work among readers met the expectations of public opinion both within France and outside it, through its barely disguised criticism of the Sun King’s policies. In addition, we cannot totally exclude the possibility that the author voluntarily circulated the manuscript.

The revocation of the royal privilege which prevented the widow Barbin from continuing the publication of the following volumes did not, however, prevent the rapid appearance of clandestine editions in large numbers to meet the growing demand of the public, despite the ban and police seizures carried out among overly reckless booksellers.

It was not until the author’s death in 1715 that, owing to the Marquis de Fénelon, grand nephew of the Archbishop of Cambrai, a new official edition was published in Paris in 1717, with the privilege, approval, and dedication to King Louis XV.

If the choice of context set in the Homeric myths of ancient Greece echoes the classicism so characteristic of the 17th century, it already prepares the way for the Age of Enlightenment in that it makes any religious legitimation of royal power impossible. This was quite unlike what Bossuet had composed in his Politics Drawn from the Very Words of Sacred Scripture.

If the work is known as a criticism of absolutism and the politics of King Louis XIV, it soon made the Archbishop of Cambrai what without doubt he never had been, namely an adversary of the monarchy. This was the result of the political use made of his book in the century of the French Revolution.

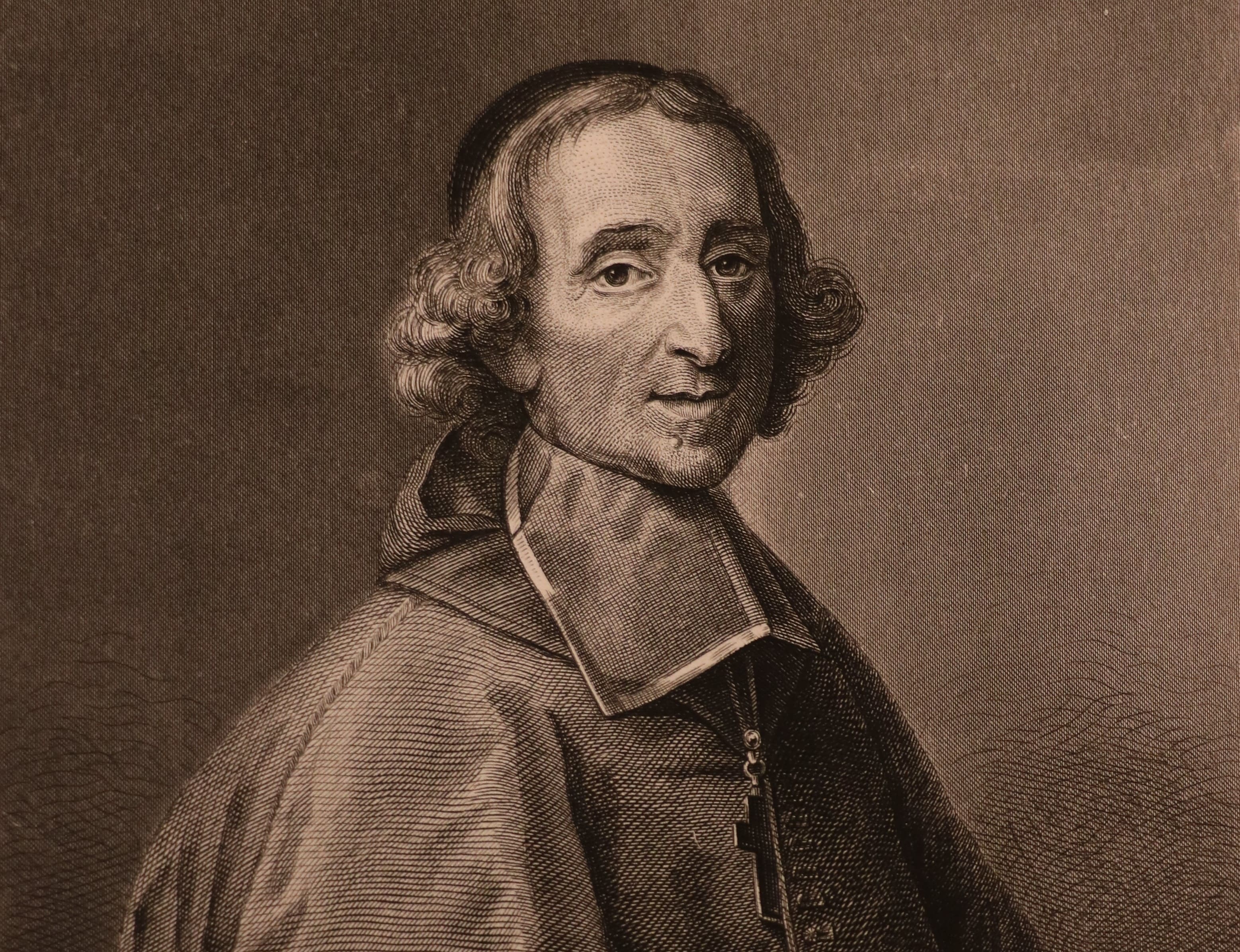

François de Salignac de La Mothe Fénelon, Archbishop of Cambrai

François de Salignac de La Mothe Fénelon, Archbishop of Cambrai

Mr. Zakaria HILAL is the Archivist of the Society of the Priests of Saint Sulpice in Paris

(English Translation by Ronald D. WITHERUP, PSS)