Madame Guyon: The History of a Mystic

Jeanne-Marie Bouvier de La Motte, more commonly known as Madame Guyon, is the name of a French Catholic mystic whose religious thought, described as "quietist," was condemned by the Church of France in 1695.

Jeanne-Marie Bouvier de La Motte, more commonly known as Madame Guyon, is the name of a French Catholic mystic whose religious thought, described as "quietist," was condemned by the Church of France in 1695.

Born in Montargis on April 13, 1648, she was the daughter of Claude Bouvier, Seigneur de La Motte Vergonville and Jeanne Le Maistre de La Maisonfort. Her father was Master of Petitions to Queen Anne of Austria, and then King's Prosecutor in the bailiwick of Montargis. Her parents entrusted her education to various religious communities in her native town, where she stayed until the age of 11. Among the nuns, she discovered the life and works of Jeanne de Chantal and Saint Francis de Sales, whose writings would influence her for the rest of her life. On January 18, 1664, she married Jacques Guyon, son of the wealthy builder of the Briare canal, linking the Seine to the Loire. Twenty-two years her senior, Jacques Guyon took Jeanne-Marie under his roof when she was 16.

In 1668, she met the Duchesse de Béthune-Charost, daughter of the former finance superintendent Nicolas Fouquet, who was forced into exile by her father's disgrace. She came to live with Madame Guyon's father in Montargis. The duchess, whose name was Marie Fouquet, became a close friend of Madame Guyon. Trained at the school of Jacques Bertot, who had attended the Caen Hermitage founded by the famous mystic Jean de Bernières, Marie Fouquet was one of Madame Guyon's major sources of inspiration in terms of mysticism.

Madame Guyon’s marriage, which could best be described as unhappy, was punctuated by many hardships. In 1670, she contracted smallpox while nursing her eldest son. The highly contagious disease spread to her youngest son, who did not survive. Her three-year-old daughter, the youngest of the siblings, recovered, while her mother was left disfigured by the after-effects of smallpox.

In 1674, she gave birth to another son, followed by a daughter, Jeanne-Marie. The latter would accompany her on her travels when her life took a new turn.

The turning point came with her husband's death on July 21, 1676, leaving the young mother a widow at just age 28. She was left with a considerable fortune and several dependent children. Against the advice of her family, she refused to remarry and decided to devote her widowhood to works of piety and charity.

In 1681, she left Montargis on the advice of Bishop Jean d'Arenthon d'Alex of Geneva, whom she had met in Paris. He asked her to take charge of a new Catholic community in Gex, in his diocese. She arrived in July of that year, and spent a long two-year stay there, which convinced her not to accept the appointment as superior of the “New Catholics” (Nouvelles-Catholiques). It is said that Madame Guyon was shocked by the methods of forced abjuration of the Protestant faith used against certain members.

In the region of Gex, Madame Guyon reunited with Father François Lacombe, whom she had met in Montargis in 1671. He became her spiritual director.

In 1683, she left Gex to settle in Thonon with a community of Ursuline nuns, where she became an advocate of mysticism, which further alienated her from Msgr d'Arenthon. It was in Thonon that she wrote her first mystical treatise, The Torrents (Les Torrents). It was not published until 1704. She left the town in autumn 1683 to set off for Turin. In the spring of 1684, Madame Guyon returned to Grenoble, where she published anonymously her text, A Short and Very Easy Way to Pray (Moyen court et très facile de faire oraison). This work, in which she celebrated her doctrine of pure love and her method of passive prayer, was such a success in the Diocese of Grenoble, and particularly within several local religious communities, that it finally upset the local Jansenist bishop, Msgr Étienne Le Camus. He criticized her for setting herself up as a "director of conscience." He asked her to leave his diocese in the spring of 1685. At the same time, she attracted the hostility of the entire Jansenist party, which was profoundly anti-mystical.

She drew on a certain French tradition of her time, with figures such as the Capuchin Benoît de Canfeld, the Carmelite friar Jean de Saint-Samson, and the lay but no less mystical Jean de Bernières, traditions to which she added certain ideas drawn from Saint John of the Cross.

Dismissed, she resumed her wanderings, which took her from Marseille to Verceil in Piedmont, where she joined her confessor, Father Lacombe. She stayed with him for a year, before setting off with him for Paris. The two arrived in the capital in July 1686. Meanwhile, the leader of Quietism, Father Miguel de Molinos, was detained in Rome, where he had good reason to worry, since his works, which had received the Imprimatur 12 years earlier, would eventually be condemned for heresy by the Congregation of the Holy Office. It seems that Madame Guyon never met Father de Molinos personally, but we do know that the success of his works extended beyond the borders of his native Aragon. There are, however, astonishing similarities in the ideas and method of payer that Madame Guyon disseminated, with those of the unfortunate Spanish mystic forced to recant, and then condemned to perpetual imprisonment in 1687.

Back in Paris, Madame Guyon lived in the Cloister of Notre-Dame district on the Île de la Cité. She received many guests and continued to spread her ideas. She was reunited with her friend, the Duchesse de Béthune-Charost, who gave her even greater access to the elite of the Court.

In January 1688, by order of the Archbishop of Paris, Msgr Harlay de Champvallon, she was brutally interned at the Visitation Convent in the Faubourg Saint-Antoine, where she was pressured to recant. She was separated from her daughter Jeanne-Marie, who had accompanied her on all her travels. The reason for her detention may have been a dispute between her half-brother, Father de La Motte, and her spiritual director, Father Lacombe, after Madame Guyon stopped taking in her half-brother, but the matter remains obscure....

Madame Guyon owed her release to her cousin Mademoiselle de La Maisonfort, a boarder at Saint-Cyr. The latter had sought the help of Madame de Maintenon, the secret wife of Louis XIV, who was behind the founding of the boarding school. La Maisonfort asked Madame de Maintenon for her cousin's release, which she succeeded in obtaining.

Madame Guyon was then accepted at Saint-Cyr, where she was persuasive to the king's wife, who wanted to take advantage of her presence at the royal boarding school. The boarding school educated young girls from the aristocracy, who were either penniless or orphans.

Nearby, at the Château de Beynes, Madame Guyon met the Abbé François de la Motte Fénelon for the first time in October 1688. He recognized in her a woman touched by grace.

Madame de Maintenon and Abbé de Fénelon both fell under the spell of Madame Guyon, who found Saint-Cyr a privileged outpost from which to exercise her mystical apostolate.

Madame de Maintenon, who was experiencing moments of dryness in her faith life, read the text A Short and Very Easy Way to Pray, a book which was of great benefit to her. At the same time, she made Father Fénelon one of her spiritual directors. He encouraged her reading, and the whole boarding school became fascinated with Madame Guyon's writings.

Meanwhile, Guyon’s book was placed on the Index in 1689, two years after Father Molinos' writings were condemned in Rome.

In 1691, Madame de Maintenon finally took umbrage at Madame Guyon's growing influence and authority at Saint-Cyr. Influenced by her other confessor, Monseigneur Godet des Marais, Bishop of Chartres, who sought to undermine his rival Fénelon, she eventually ordered the dismissal of Madame Guyon, and then of Abbé Fénelon himself. After the latter's departure, the boarding school was cleared of all Guyon’s books.

Madame Guyon continued to make a name for herself, however, as she was supported by several publishers who ensured the distribution of her works, which became increasingly popular throughout the kingdom.

It was at this point that Bossuet entered the scene, at the request of both Fénelon, who was hurt at having been spurned, and Madame de Maintenon, who was seeking to have the Quietism of Madame Guyon's mysticism condemned. “The Eagle of Meaux,” as he was called, began examining her writings in August 1693. He delivered his verdict in March 1694, condemning her doctrine.

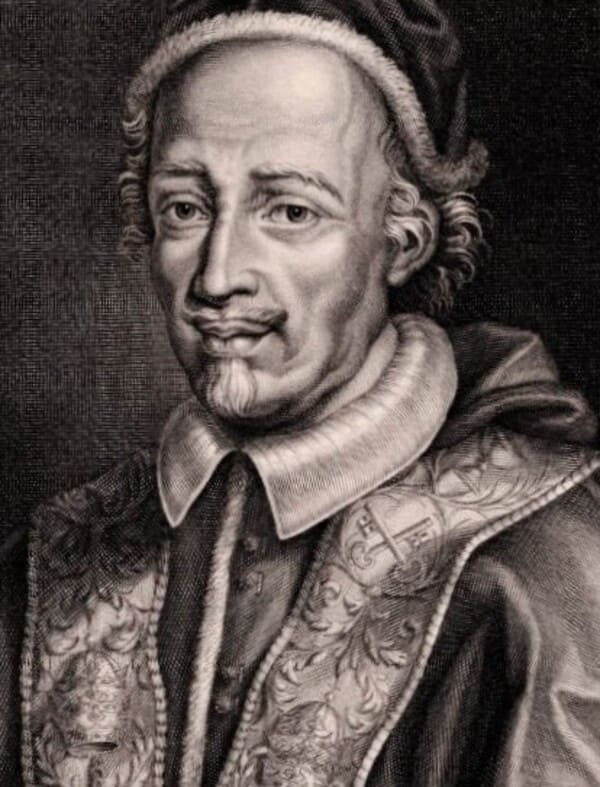

Jacques Bénigne Bossuet, Bishop of Meaux

A commission was subsequently set up in July 1694. Its task was to examine Madame Guyon's ideas and works. It included Msgr Bossuet, Bishop of Meaux, Cardinal de Noailles, Bishop of Châlons, and Monsieur Louis Tronson, Sulpician Superior of the Seminary of Saint-Sulpice and Sulpician Superior General. The Sulpicians' home in Issy, near Paris, provided the ideal setting for the work of this commission, which lasted several months and became known as the "entretiens" or "conferences at Issy." A plaque commemorating these "Entretiens d'Issy" is still preserved at the Séminaire Saint-Sulpice in Issy-les-Moulineaux.

Louis Tronson Fénelon and his protégée, Madame Guyon, were not invited to take part in the work of this commission. This did not prevent Madame Guyon from writing Justifications, a kind of apologia, while Fénelon prepared a defense of his directee, emphasizing the mysticism of great saints such as Saint Francis de Sales and Saint Theresa of Avila.

The Archbishop of Paris, Msgr Harlay de Champvallon, did not wait for the commission’s work to be completed. After the first conferences, he issued a decree in October 1694 condemning Madame Guyon's writings.

Thinking Bossuet sympathetic to her cause, she sought his protection at the Visitation de Meaux convent in January 1695, where she met him several times to convince him of the purity of her ideas. Bossuet, for his part, tried to get her to confess her heresy, but was unsuccessful.

The following month, Fénelon became a bishop. He was appointed Archbishop of Cambrai on February 4, while the conferences resumed to Issy. In March 1695, Msgr de Fénelon was invited to the last session of the “Conferences at Issy,” which resulted in a severe condemnation of Madame Guyon's Quietism. The Conferences at Issy

Forced to do so, Fénelon and Madame Guyon signed their adherence to the 34 articles of Issy, which did not prevent Madame Guyon's arrest a little later in December 1695. She was suspected of having resumed her mystical teachings. She was imprisoned in Vincennes. Released in October 1696, she was placed under house arrest in a small house in the village of Vaugirard near Paris. Attempts were made to have Msgr de Fénelon testify against her, but he refused. On the contrary, he wrote his text, Maxims of the Saints on the Interior Life (1697), which Louis XIV succeeded in having condemned by Rome, with Bossuet's help. The Eagle of Meaux, favored by the king and his wife, sought to undermine Fénelon’s book by publishing his own book, An Analysis of Quietism (Relation sur le Quétisme) in June 1698. In it he used documents that Madame Guyon had entrusted to him under the seal of secrecy that characterizes sacramental confession. Just as Bossuet published his Relation, Madame Guyon was once again arrested, and subsequently imprisoned.

At the Bastille, she was subjected to intense interrogations by Nicolas de La Reynie himself, the man who had successfully reformed police institutions, making Paris a very safe city. Once again, Madame Guyon managed to avoid all the traps set for her. Despite the unsuccessful investigation that exonerated her, Madame Guyon had to wait until March 1703 before she could regain her freedom.

Allowed to move in with her son near Blois, where her residence was under surveillance, she kept up numerous epistolary relations with the friends who had remained loyal to her, foremost among them the disgraced “Swan of Cambrai” (Fénelon). While still in Blois, she continued to write, completing the autobiography she began in 1688 in the glory days of Saint-Cyr, when she was favored by the King's wife.

She breathed her last in Blois on June 9, 1717. Between 1712 and 1720, her works were distributed by her friend Pastor Pierre Poiret, and her spiritual letters were published in 1767 by Pastor Duthoit-Mambrini from Vaudois.

Quietism and Gallicanism

The Issy Conferences should not only be analyzed from a doctrinal and religious standpoint. This major event in the history of the French Church under the Ancien Régime also merits a political analysis of the relationship between the King of France and the Sovereign Pontiff.

It all began in 1673 with the “Regale Affair” (L’affaire de la régale), concerning the revenues of vacant abbeys and bishoprics, which the king claimed to enjoy until a new bishop or abbot was invested. This conflict, which pitted him against Pope Clement X and then Innocent XI, reached its climax with the Declaration of the Four Articles adopted by the Assembly of the Clergy of France in 1682.

Drafted largely by the new Bishop of Meaux and celebrated orator Jacques Bénigne Bossuet, a rising figure in the French episcopate, the Declaration listed the freedoms of the Gallican Church. It aimed to confine the Bishop of Rome to purely spiritual prerogatives. The Four Articles went so far as to assert that ecumenical councils are superior to the authority of the Pope, who cannot contradict them despite the primacy of the See of St. Peter. Louis XIV thus sought to weaken papal power by asserting his right to oversee the religious affairs of his kingdom.

This major event in the history of Gallicanism paved the way for the question of papal infallibility, which would not be resolved until the following century, when Vatican Council I sanctioned the growing power of the Pope and ultramontanism in 1871.

Innocent XI reacted to the Four Articles by refusing to give canonical investiture to bishops appointed by Louis XIV, as provided for in the Concordat of Bologna (1516), thus disrupting religious life in France.

It was not until 1693 that the conflict between the Papacy and France came to an end with the accession of Innocent XII to the See of Rome.

The fate reserved for Molinos, condemned in 1687 by the Holy Office for Quietism, prompted Louis XIV to align himself with this line in order to promote the resolution of his conflict with Rome. This may well explain Madame de Maintenon's change of heart with regard to Madame Guyon in 1691.

The Fénelon Collection in the Archives of Saint Sulpice in Paris

The Archives of Saint Sulpice hold two major documents relating to the Conferences of Issy.

Manuscript 2134 is a copy of the 34 articles. The work of the commission concludes with a document "deliberated in Issy on March 10, 1695 and signed Jacques Bénigne Bishop of Meaux, Louis Antoine, Bishop of Châlons, François de Fénelon named Archbishop of Cambrai." The signatures of Louis Tronson, host of the conferences, and Bossuet are appended below the 34th article.

Bossuet's initials can be found in the margins or at the bottom of most pages, proving that he presided over the work of this commission.

The 34 articles are followed by a transcript of Madame Guyon's act of retraction, signed "Jeanne Marie Bouvier de La Motte de Guyon", in which Bossuet enjoins her "not to write any book, nor to teach or dogmatize in the Church, nor to lead souls in the ways of prayer or otherwise [...]. Done at Meaux in the monastery of the Visitation Sainte Marie this April 15, one thousand six hundred and ninety-five." The locale was the monastery to which she had retreated in order to be able to meet Bossuet and try to influence him.

In the transcript of the second retraction, dated July 1, 1695, Madame Guyon acknowledges the condemnation of her Moyen court and Song of Songs (Cantique des cantiques). She also asserts that copies of her work Les Torrents had been so altered and falsified that she denied its authorship.

These two retractions, signed by the condemned woman, are followed by transcriptions of two attestations delivered by the Bishop of Meaux to Madame Guyon on the same dates: April 15 and July 1, 1695, in which Bossuet acknowledges her submission.

The transcription of these acts is preceded by the marginal notes "N. M. Phélipeaux reports this act." Is this the Secretary of State for the King's Household, Louis II Phélypeaux de Pontchartrain [1690-1699]? This could well be the case, given that the Department of the King's Household became responsible for clergy affairs in 1661, not to mention the role played by the King's wife in this affair.

On the other hand, manuscript 2005, which is in fact an artificial collection linking together several archival items, is another valuable source of information for understanding the process that led to the 34 articles.

Comprising 16 pieces, many of them originals, an analysis of this collection reveals that the first working sessions resulted in 30 articles presented by Bossuet to the Abbé de Fénelon, who was prepared to sign them on condition that a few clarifications were made. Subsequent sessions brought these clarifications, with the addition of 4 articles, bringing the total to 34.

We can also see that, far from ending, the conflict between the Eagle of Meaux and the Swan of Cambrai had its consequences. This is particularly clear in Exhibit 13, entitled "Articles proposed by the Archbishop of Cambrai to the Archbishop of Paris in the presence of Madame de Maintenon, of which he is not unhappy." This piece is dated February 1697, before the publication of his Maxims of the Saints, in which he was to defend Madame Guyon. Fénelon also involved Rome in this publication, for which he requested the support of the Holy Office. But despite the spiritual justifications he provided in his Maxims, Rome sided with the Bishop of Meaux.

Deemed unreadable by public opinion, Fénelon's Maxims were not as successful as Bossuet's response, published a year later: An Analysis of Quietism (1698). The style that the great orator from Meaux purposely employed in his work drew a host of laughs from both the common people and the Court.

Mr. Zakaria HILAL, Archivist of the Society of the Priests of Saint Sulpice – Paris

Translated by Rev. Ronald D. WITHERUP, PSS