Father Jacques-André EMERY, pss (1732-1811)

Sulpicians consider Emery a “second founder” of the Society, as he found the ways to save the Society in the wake of the French Revolution and its violent aftermath.

Did Father Emery’s family roots already orient him toward the open and expansive ministry that he fulfilled from the viewpoint of both religion and politics? Emery was a native of Gex, a little city that lies at the juncture of several types of territory and diverse cultural and religious influences. The Geneva of John Calvin is only a short distance away!

What aspects of his personality made the General Consultors choose Emery as Superior General on 10 September 1782 after the resignation of Father Pierre Le Gallic? His family, tied to the nobles of the area, decided first to entrust Emery’s education to the Carmelites, who were established in Gex, and then later to the Jesuits at Mâcon. Noted for his refined manner and intelligence, he entered the Seminary of Saint-Irénée in Lyon, then presented himself to the competitive exams at the Robertins College in Paris, a house of formation maintained by the Sulpicians. Emery was ordained a deacon on 4 June 1757, entered the Sulplician Solitude, and then was ordained a priest on 11 March 1758. We should emphasize that Emery did not obtain his clerical formation at Le Grand Séminaire of Paris but at Robertins College. This explains, in part, the problems of governance during the early years of his being Superior, about which we will have more to say later.

City Hall of Gex

City Hall of Gex

Before his election to the Generalate, his abilities in discernment, a solid interior life, and a particularly pronounced sensitivity to diplomacy often enticed his superiors to give him delicate tasks, such as spending time at the seminary in Orléans, which was under the spell of Jansenism. Then from 1764 he was again at the Seminary of Saint Irénée in Lyon, a city in which even the archbishop was favorable to some Jansenist theories. The competence and extreme lucidity with which he was able to manage some of these crises are remarkable. In 1776 he was named Superior of Le Grand Séminaire in Angers. There he reestablished the discipline that had tended to lapse. In 1777, elected a General Consultor (assistant) – indeed the youngest of the assistants –, his later election as Superior General broke a longstanding tradition that the Superior General normally came from Le Grand Séminaire in Paris.

In Paris, if most of the houses maintained by Saint Sulpice were calm, that was not the case with Le Grand Séminaire. Coveted by ambitious young men of the upper gentry (« Fils de Famille »), the seminary had become by reputation an « episcopal seedbed, » with the consequence that lack of adherence to the Rule had upset preceding Superiors General, Fathers Jean Cousturier, Claude Bourrachot and Pierre Le Gallic. As soon as Emery was elected, he set in motion a strong regimen of strict reform, oriented toward a return to the fundamental spiritual intuitions of Father Jean-Jacques Olier and to the rules of interiority established by Father Louis Tronson, third Superior General. Can one find in this reform the model that was largely employed during the 19th century? There was no lack of numerous obstacles to achieve the goal of reform: attempted plots, assassinations of character, and calumnies. But nothing deterred the Superior General’s determination. Indeed, on the eve of the French Revolution, Le Grand Séminaire of Paris had basically rediscovered a true spiritual flourishing. Assuredly, Emery often stayed in the capital to anticipate and forestall anything from getting out of hand, yet he made systematic visits to the provincial seminaries outside Paris. Emery’s efforts were rewarded by the invitation for Saint Sulpice once again to assume the direction of the seminary in Reims in 1787. All this has helped some historians reach the conclusion that at the dawn of the Revolution there was a slight improvement in the Christian faith and the quality of spiritual and intellectual formation in France.

The Revolution is the period during which Father Emery reveals his profound attachment to Christ and to the Church and the quality of his abilities of discernment. On 14 July 1790, on « the feast of the (birth of the) nation, » the seminarians and formators were experiencing a fair amount of tension. Several serious problems arose at the moment Father Emery was forced to accept housing some « deputies » at the seminary, and the seminarians were conscripted for work on the embankments at the Champ de Mars. The atmosphere was also very tense at the General Assembly of the Society of Saint Sulpice in August, 1790. The only tentative hope was the promise of opening a seminary in the newly erected diocese of Baltimore in the United States, at the invitation of the first bishop, John Carroll.

Bishop John Carroll, First Bishop of the United States

Bishop John Carroll, First Bishop of the United StatesThe « black years » began primarily with the categorical refusal of Emery and the entire group of priests of Saint Sulpice to pledge allegiance to the Civil Constitution of the Clergy. The words of the Superior General are without ambiguity: « It is the triumph of the Gallican Church. » From that moment on, a chain of sad events followed, especially in 1791 the closing of practically all the seminaries entrusted to Saint-Sulpice in France. Paris still resisted, but how long would that last? Sensing the risks involved, Father Emery decided to transfer the archives of the Society, and anything of great value in the seminary, to the residence of a relative, Madame de Villette, who lived in an apartment previously inhabited by Voltaire. The revolutionaries never thought to search there; thus the documents were fortunately preserved for us today.

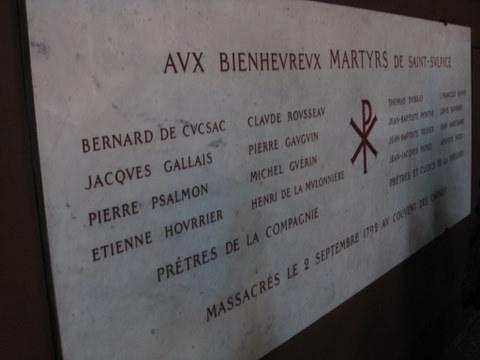

On 15 August 1792, a large number of seminarians and formators who were staying at the seminary in Paris were arrested and sent to the Carmes, where a certain number of them were martyred on 2 September (now the commemoration of the Blessed Sulpician Martyrs).

Monument to the Blessed Sulpician Martyrs of Saint Sulpice

On 4 September Father Emery decided to close the seminary of Paris permanently, though he himself wanted to stay there. Thus erupted the affair of his assent to the text of the legislative assembly of 3 September 1793. One of the articles stipulated: « Every Frenchman must take the oath to maintain with all his ability liberty, equality, and the protection of people and property, and if necessary, to die for maintaining the Law ». Being a refined thinker and knowing his fundamental moral theology, Emery proposed that it was necessary to properly interpret the words « liberty » and « equality », and in accord with his conscience, there was nothing to prevent someone from taking the oath. Certain people did not make the same judgment and were greatly disturbed by this approach, in particular, Bishop Jean-Seffrein Maury who lived in Rome.

Bishop Jean-Seffrein Maury

Bishop Jean-Seffrein Maury

In the end, however, Emery’s ingenious diplomacy, proved insufficient, for he was arrested and imprisoned for the first time from 19 to 31 May 1793. Then again he was imprisoned on 13 July the same year and brought before the Revolutionary Tribunal on 14 August. During his time in prison, he became instrumental in bringing back to communion with the Roman Church priests who had sworn the oath and renounced all their ministry. He was never executed, probably owing to the intervention of several who supported him.

His openness earned him neither rest nor the gratitude of his Sulpician confreres. He was suspected of having collaborated too much with the authorities, in particular, regarding his position concerning the repression of the royalist insurrection of 18 Fructidor,** Year V, for which he was strongly reproached, even by Father François Nagot, the Superior in Baltimore, in a very severe letter. Thus he experienced trials, abandonment, and solitude. A certain distance from all this allowed him to return to his research. He published several works in theology, including The Practice of the Vow of Poverty, a résumé of the theses of Francisco Suarez, the great 16th century theologian, and The Christianity of Francis Bacon.

The coup d’état of 18 Brumaire** and the signing of the Concordat of 1801 finally yielded the possibility for the Catholic Church in France to regain some hope. It was necessary to reconstruct everything, often by means of luck, and with a very reduced number of formators. The idea arose to recall the Sulpicians from Baltimore but was abandoned. The series of houses in which the seminary of Paris was established barely sufficed. It was only with the opening of the school year in 1803 that a real solution was found, with the purchase of an old house of the « Teaching Sisters » (Sœurs de l’Instruction) on the rue Pot-de-Fer. One should remember the energy with which Emery, this man of seventy years of age, undertook to restore the destiny of the Society and to reestablish vigorously the same measures he had done twenty years prior! The fruits of these efforts were not long in coming, both in Paris and in the provincial seminaries where Saint Sulpice once again took charge of priestly formation. In addition, the old patrimony of the property at Issy was gradually re-bought and, through private means, preserved for future use.

The Sulpician Seminary at Issy-les-Moulineaux

The Sulpician Seminary at Issy-les-MoulineauxAs we come to the end of this bicentennial year of Emery’s death (2011), it is important to reassess him, one of the most emblematic figures of our Society. Certainly the qualities of the personality of Jacques-André Emery permitted him to follow this exceptional and moving path. But would he have been able to do this without a well established spiritual foundation, as his notebooks from the time of his being Superior in Paris before the Revolution testify? The will for « reform » which gave impetus to those years was refound the next day in the throes of the revolutionary period. His use of the works of Olier – he often meditated on the Pietas Seminarii – and his attachment to the minute teachings of Tronson, without forgetting his philosophical training, certainly contributed to the forging of a « synthesis » which largely inspired his successors in the 19th century. Let’s not forget, too, that the foundation in Baltimore started from the beginning with determination – even if afterwards there were some tensions with Bishop Carroll concerning the nature of the primary Sulpician mission in his diocese. There remain especially the determination and courage with which Father Emery knew how to endure, notably during the worst years he experienced from 1791 to 1796. It is the revelation of Emery’s prayerful attachment to Christ and to the Church that is essential, an attachment which permits certain priests once more to find their path to ecclesial communion. Emery’s opposition to Gallican politics of the oath of the Civil Constitution, and his bold refusal to support the Napoleanic projects for a national church, witness together the strength of his convictions. One thing is certain: such a great Sulpician personality warrants his own critical biography, a task on which the Commission for the Study of Sources and Tradition plans to work in the future. We await the answer to our prayer for this resource. (11 November 2011)

**One of the excesses of the aftermath of the French Revolution was abandonment of the Gregorian calendar and changing the reckoning of time in the Republican period. Years were calculated from the beginning of the Revolution (14 July 1789), and the months were renamed. Fructidor extended from mid-August to mid-September, and Brumaire from 22 October to 22 November.

N.B.: The article is copyrighted (© 2011) and cannot be reproduced in any form without the expressed written permission of the author. It is part of a larger study that will be conducted by the Commission.